The Philippine God's and Godesses

What exactly is Philippine mythology?

Philippine mythology is a collection of stories and superstitions about magical beings a.k.a. deities whom our ancestors believed controlled everything.It’s part of the folklore, which covers all kinds of traditional knowledge embedded in our society: arts, folk literature, customs, beliefs, and games, among others.

Folk narratives are all about stories. They may be told in prose, verse, or both. They are further divided into three sub-categories: the folktales or kuwentong bayan, legends or alamat, and myths.

The folktales are pure fiction, something that you use to entertain bored kids. The legends and myths, meanwhile, are assumed to be true by the storyteller. It’s the timeline that sets them apart.

While legends happened in a much more recent time period, myths are believed to have taken place in the “remote past,” meaning a period when the world as we know it today wasn’t fully formed yet.

According to the late Damiana L. Eugenio, the Mother of Philippine Folklore, myths “account for the origin of the world, of mankind, of death, or for characteristics of birds, animals, geographical features, and the phenomena of nature.”

Falling under this sub-category are the stories or adventures of deities, defined as supernatural beings with human characteristics.

“Some of these deities are always near; others are inhabitants of far-off realms of the Skyworld who take interest in human affairs only when they are invoked during proper ceremonies which compel them to come down to earth.”

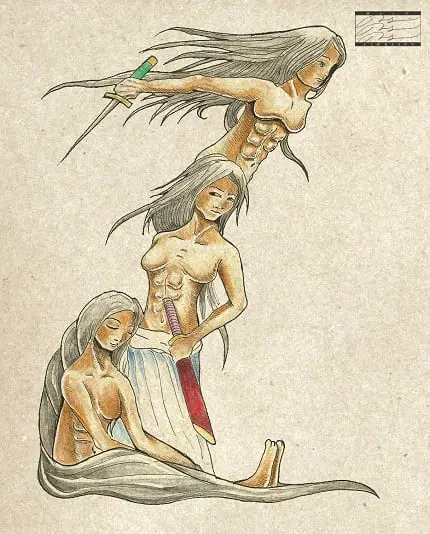

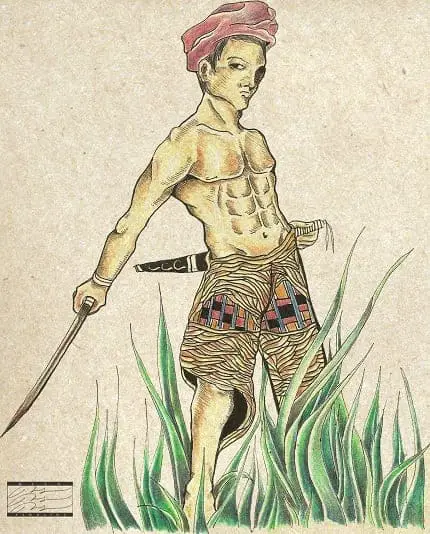

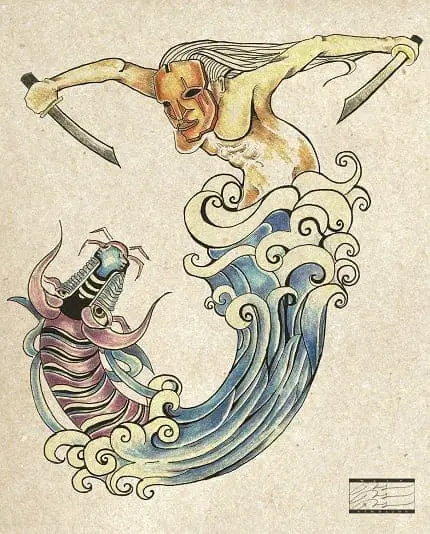

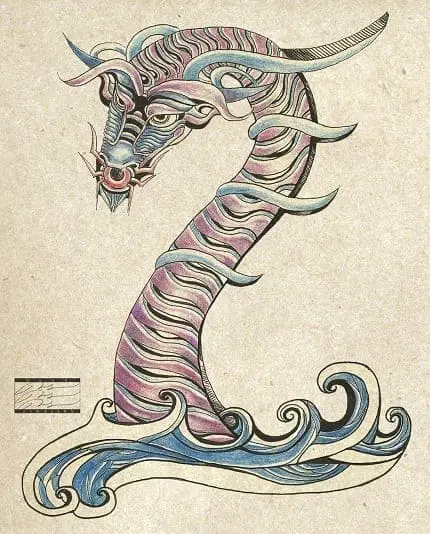

In this three-part series, you’ll get to know more about these interesting deities from Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. We’ll examine their stories, special powers, and other details that will tickle the curious child in you. Special thanks to the talented Pinoy graphic artists whose amazing works have helped bring these ancient deities back to life.

Note: All images presented in these articles are a modern depiction of our ancient deities. History tells us that representations of these gods and goddesses created by our ancestors were burned by the colonizers. Therefore, the point of these illustrations is not to “westernize” Philippine mythology but to make it more appealing and engaging to the younger readers who ought to know more about their roots.

Part I: Luzon Divinities

Based on the early accounts of Spanish conquistador Miguel de Loarca, the ancient Tagalogs believed in one creator god. However, they didn’t have the power to communicate with him directly. An intercessor or “middleman” was required.This go-between could either be the spirit of their dead relative or any one of the lower-ranking deities. Ancient gods were usually worshiped in the form of adobe carvings called likha, while the dead ancestors were revered by offering foods or gold adornments to wooden images known as anito.

Aside from the deities and the souls of the departed, the ancient Tagalogs also venerated animals like the crocodiles, believing that these wild beasts contained the human souls. On the other hand, a tigmamanukan bird flying across someone’s path was considered an omen. Depending on the direction of its flight, this bird could foretell whether an expedition would end up a success or disaster.

1. Bathala.

From his abode in the sky called Kawalhatian, this deity looks over mankind. He’s pleased when his people follow his rules, giving everything they need to the point of spoiling them (hence, the bahala na philosophy). But mind you, this powerful deity could also be cruel sometimes, sending lightning and thunder to those who sin against him.

Lesser divinities also assisted Malayari in carrying out his tasks, among them Akasi, god of health and sickness; Manglubar, god of powerful living whose task was to “pacify angry hearts”; and the guardian angel Mangalabar, the god of good grace.

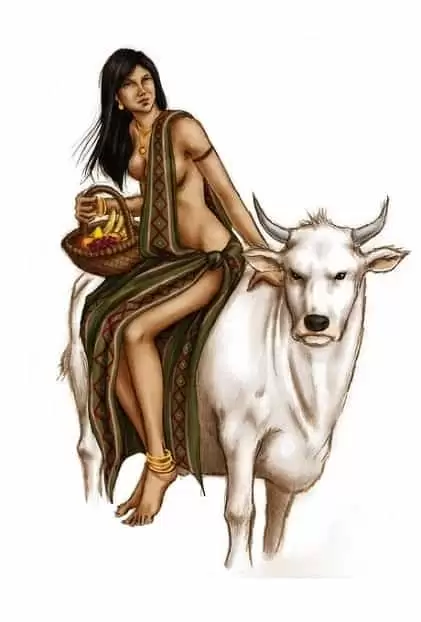

2. Idianale.

There are varying accounts as to what specific field Idianale was worshiped for. Historian Gregorio Zaide said that Idianale was the god of agriculture, while other sources suggest that she was the patron of animal husbandry, a branch of agriculture.

3. Dumangan.

In Zambales culture, Dumangan (or Dumagan) caused the rice to “yield better grains.” According to F. Landa Jocano, the early people of Zambales also believed Dumagan had three brothers who were just as powerful as him.

4. Anitun Tabu.

In Zambales, this goddess was known as Aniton Tauo, one of the lesser deities assisting their chief god, Malayari. Legend has it that Aniton Tauo was once considered superior to other Zambales deities. She became so full of herself that Malayari reduced her rank as a punishment.

The Zambales people used to offer her with the best kind of pinipig or pounded young rice grains during harvest season. Sacrifices that made use of these ingredients are known as mamiarag in their local dialect.

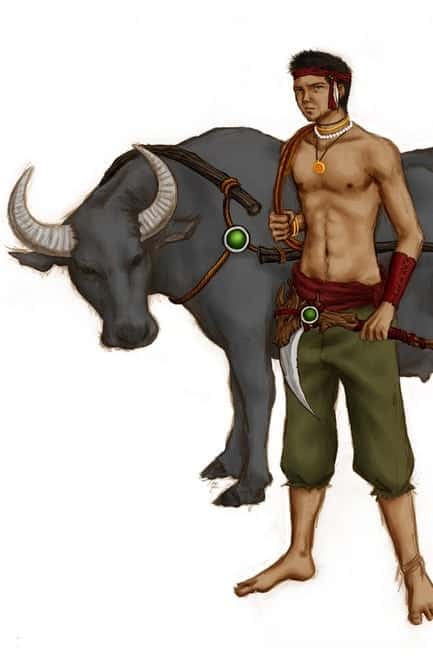

5. Dumakulem.

This Tagalog sky-god later tied the knot with another major deity, Anagolay, known as the goddess of lost things. The marriage produced two children: Apolaki, the sun god, and Dian Masalanta, the goddess of lovers.

6. Ikapati/Lakapati.

Some sources describe Lakapati as androgynous, hermaphrodite, and even a “transgender” god. In William Henry Scott’s “Baranggay,” Lakapati is described as a major fertility deity represented by a “hermaphrodite image with both male and female parts.”

Also Read: The “Masuso” Pots of National Museum

Before planting in a new field, the ancient Tagalogs usually offered sacrifices to Lakapati. In a 17th century report by Franciscan missionary Father

Pedro de San Buenaventura, it was said that a farmer paying homage to

this fertility goddess would hold up a child before saying “Lakapati pakanin mo yaring alipin mo; huwag mong gutumin” (Lakapati, feed this thy slave; let him not hunger).Being the kindest among the lesser deities of Bathala, Lakapati was loved and respected by the people. She married the god of seasons, Mapulon, and became the mother of Anagolay, goddess of lost things.

7. Mapulon.

Not much is known about this deity, aside from the fact that he married Ikapati/Lakapati, the fertility goddess, and sired Anagolay, the goddess of lost things.

8. Anagolay.

When she reached the right age, she married the hunter Dumakulem and gave birth to two more deities: Apolaki and Dian Masalanta, the ancient gods of sun and lovers, respectively.

Interesting fact: In September of 2014, the Minor Planet Center (MPC), the international agency responsible for naming minor bodies in the solar system, officially gave the name (3757) Anagolay to an asteroid first discovered in 1982 by E. F. Helin at the Palomar Observatory.

Also Read: A Planet Named After A Filipino

Obviously,

the asteroid was named after the ancient Tagalog goddess of lost

things. The name, submitted by Filipino student Mohammad Abqary Alon,

bested more than a thousand entries in a contest held by the Space

Generation Advisory Council (SGAC).9. Apolaki.

Early people of Pangasinan claimed that Apolaki talked to them. Back when blackened teeth were considered the standard of beauty, some of these natives told a friar that a disappointed Apolaki had scolded them for welcoming “foreigners with white teeth.”

In a book by William Henry Scott, the name of this deity is said to have originated from apo, which means “lord,” and laki, which means “male” or “virile.” Jocano’s Outline of Philippine Mythology details how Apolaki came to be: He was the son of Anagolay and Dumakulem, and also the brother of Dian Masalanta, the goddess of lovers.

In other stories, however, Apolaki was, in fact, the son of the supreme god of the ancient Tagalogs, Bathala. The book “Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales” by Maximo Ramos contains the story of how the sun became brighter than the moon. In the said myth, Bathala sired two children from a mortal woman. He named his son Apolaki and his daughter Mayari.

Both children had eyes so bright that they became the source of light for the rest of the world. When Bathala died, Apolaki and Mayari both wanted to succeed their father. A long, bloody argument ensued as neither one of them wanted to give up the throne. The fight reached the boiling point when Apolaki hit Mayari‘s face with a wooden club, blinding her one eye.

Cooler heads prevailed, and both agreed to just take turns in ruling the world. Apolaki now occupies the throne during daytime while Mayari, the moon goddess, provides the “cool and gentle light” during nighttime, for she is blind in one eye.

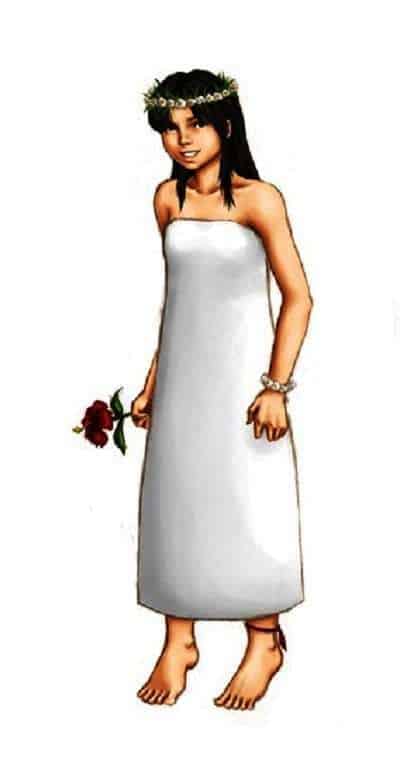

10. Dian Masalanta.

Sacrifices were offered to Dian Masalanta to ensure successful pregnancies. The same was done for other lesser deities who ruled specific domains, like Mankukutod, the protector of coconut palms who could cause accidents if the offering was not made. Haik, the sea god, was honored by sea travelers for a safe and successful voyage, while Uwinan Sana, the forest deity, was acknowledged so that anyone who entered his “property” wouldn’t be punished for trespassing.

11. Amanikabli.

In the book Barangay by William Henry Scott and the 1936 Encyclopedia of the Philippines by Zoilo Galang, Amanikabli was identified as the Tagalog anito of hunters who rewarded his worshipers with a good game.

The chief protector of the sea, on the other hand, was Aman Sinaya (or Amanisaya in other references), who “gave his devotees a good catch.” In the same book by William Henry Scott, Aman Sinaya was described as the deity called upon by believers “when first wetting a net or fishhook.” He was also identified as the father of Sinaya who invented the fishing gear.

The works of anthropologist F. Landa Jocano beg to differ. According to his relatively more modern version, Amanikabli was one of the lesser deities assisting Bathala in Kawalhatian. He was described as “the husky, ill-tempered ruler of the sea,” whose hatred towards mankind started when a beautiful mortal woman, aptly named Maganda, rejected his love.

Since then, the sea god had made it his personal agenda to send “turbulent waves and horrible tempests every now and then to wreck boats and drown men.”

12-14. Mayari, Hana, and Tala.

Before long, these three demigods were given specific roles: Mayari, Hana (or Hanan in other references), and Tala became the Tagalog goddesses of the moon, morning, and star, respectively.

F. Landa Jocano’s Outline of Philippine Mythology gave a flattering description of the moon goddess: She was the “most beautiful divinity in the court of Bathala.” In other Luzon myths, however, the moon deity was anything but a beautiful goddess.

Agueo and Bulan are comparable to the Bible’s Cain and Abel. Between the two, Bulan was the mischievous one. When he overheard a group of thieves wishing for darkness so they could steal and wreak havoc to mankind, Bulan was thrilled. He then asked his brother, Agueo, to quickly leave the earth so his evil friends could do their business. When Agueo refused, a heated argument took place.

Aware of everything that happened, Bathala was furious at Bulan. From his abode in the sky, he “seized an enormous rock and hurled it whistling through the air.” It hit Bulan‘s palace, breaking it into pieces. The flickering fragments became the stars. Bulan had since been banned from joining his brother in circling around the world. He still lives in a fiery palace, but its dim light is only enough to guide the thieves during nighttime.

When their father died, the siblings argued on who deserved to take the throne. The fight ended up with Mayari blinded in one eye after Apolaki hit her with a bamboo club.

Burdened by guilt, the sun god finally agreed to just share the leadership with her sister. Apolaki soon became the “sun” who provides warm light during the day, while Mayari (or the “moon”) rules every night with a cooler and dimmer light due to her blindness.

15-17. Lakanbakod, Lakandanum, and Lakambini.

Spanish lexicographers called these supernatural beings anito, Bathala‘s agents who were assigned specific functions. Three of the most interesting minor deities actually had names that rhyme together: Lakanbakod, Lakandanum, and Lakambini.

In William Henry Scott’s “Barangay,” Lakanbakod (Lakan Bakod or Lakambacod in other sources) was described as a deity who had “gilded genitals as long as a rice stalk.”

Lakanbakod was the “lord of fences,” a protector of crops powerful enough to keep animals out of farmlands. Hence, he was invoked and offered eels when fencing a plot of land.

Lakambini was just as fascinating. Although the name is almost synonymous with “muse” nowadays, it was not the case during the early times.

Up until the 19th century, lacanbini had been the name given to an anito whom Fray San Buenaventura described as “diyus-diyosang sumasakop siya sa mga sakit sa lalamunan.” In simple English, this minor deity was invoked by our ancestors to treat throat ailments.

Every year during the dry season, the natives would make sacrifices for the water god to give them rain. And when the rain started pouring, they would take it as a cue that Lakandanum had returned, and everyone would be in a festive mood.

In fact, the old Kapampangan new year called Bayung Danum (literally means “new water”) started as a celebration in honor of Lakandanum. When Christianity came into the picture, it was converted into the feast of St. John in Pampanga and feast of St. Peter in other areas.

18-19. Galang Kaluluwa and Ulilang Kaluluwa.

In some Tagalog creation myths, Bathala was not the only deity who lived in the universe before humanity was born. He shared the space with two other powerful gods: the serpent Ulilang Kaluluwa (“orphaned spirit”) who lived in the clouds and the wandering god aptly named Galang Kaluluwa.

Ulilang Kaluluwa wanted the earth and the rest of the universe for himself. Therefore, when he learned of Bathala who was eyeing for the same stuff, he decided to fight. After days of non-stop battle, Bathala became the last man standing. The lifeless body of Ulilang Kaluluwa was subsequently burned.

A few years later, Bathala and Galang Kaluluwa

met. The two became friends, with Bathala even inviting the latter to

stay in his kingdom. But the life of Galang Kaluluwa was cut short by an

illness. Upon his friend’s request, Bathala buried the body at exactly the same spot where Ulilang Kaluluwa was previously burned.

Soon, a mysterious tree grew from the grave. Its fruit and wing-like leaves reminded Bathala of his departed friend, while the hard, unattractive trunk had the same qualities as the evil Ulilang Kaluluwa.

The tree, as it turned out, is the “tree of life” we greatly value today–the coconut.

Also Read: 7 Philippine Fruits You Probably Don’t Know

It

didn’t take long before they discovered more of the tree’s hidden

gifts: Its leaves could turn into good mats or brooms while the fiber

could become sturdy ropes, among other things.20-21. Haliya and the Bakunawa.

Legend has it that the world used to be illuminated by seven moons. The gigantic sea serpent called bakunawa, a mythical creature found in the early Bicolano and Hiligaynon culture, devoured all but one of these moons.

In some myths, the remaining moon was saved after the gods came to the rescue and punished the sea monster. Another story suggests that Haliya was the name of the last moon standing, and she spared herself from being eaten by making noises using drums and gongs–sounds that the bakunawa found repulsive.

Believing that an eclipse was actually a bakunawa attempting to swallow the moon, ancient Visayans tried to ward off the monster by creating sounds. They did this by striking the floors of their houses or by beating cans, drums, and the like.

22. Sitan.

The modern-day heaven and hell also had ancient counterparts. Jocano said that the early Tagalogs believed good guys would go to Maca, a place of “eternal peace and happiness.” The evil sinners, on the other hand, were thrown into the “village of grief and affliction” called Kasanaan/Kasamaan.

The Kasanaan is a place of punishment ruled by Sitan, which shares striking similarities with Christianity’s ultimate villain, Satan. However, Jocano said that Sitan was most likely derived from the Islamic ruler of the underworld named Saitan (or Shaitan). This suggests that the Muslim religion already had a grip to our society way before the Spaniards arrived.

Mansisilat was literally the home-wrecker of Philippine mythology. As the goddess of broken homes, she accepted it as her personal mission to destroy relationships. She did this by disguising herself as an old beggar or healer who would enter the homes of unsuspecting couples. Using her charms, Mansisilat could magically turn husbands and wives against each other, ending up in separation.

In William Henry Scott’s Baranggay, the former was described as “the most powerful kind of witch, able to kill or cause unconsciousness simply by greeting a person.” Jocano added that a Hukluban was also a terrific shapeshifter who could make anything happen–say, burn a house down–by simply uttering it.

The Mankukulam, on the other hand, often wandered around villages pretending to be a priest-doctor. In the same book by Scott, a mankukulam was described as a “witch who appears at night as if burning, setting fires that cannot be extinguished, or wallows in the filth under houses, whereupon some householder will sicken and die.”

Ref.: https://filipiknow.net/philippine-mythology-gods-and-goddesses/

Comments

Post a Comment